For many children of my generation, there was no greater source of sleepless nights and absolute nausea-inducing horror than the Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark books. These are three books, released during the 80s, that absolutely mortified every child who ever read them. I remember trembling under my covers as the stories ran through my brain, wondering why a kind and merciful God would have ever let such unmitigated evil out into the world at all, let alone on the innocent shelves of an elementary school library.

For many children of my generation, there was no greater source of sleepless nights and absolute nausea-inducing horror than the Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark books. These are three books, released during the 80s, that absolutely mortified every child who ever read them. I remember trembling under my covers as the stories ran through my brain, wondering why a kind and merciful God would have ever let such unmitigated evil out into the world at all, let alone on the innocent shelves of an elementary school library.As anyone familiar with these books knows, it wasn’t the stories themselves that were the scary part. They were reasonably frightening, sure, very short and to the point, each of them written by Alvin Schwartz, a professional folklorist. I was a little frightened as a child that every single one had extensive footnotes—it made me feel like somewhere, somehow, these horrible events might have actually happened. But the stories were hardly enough to terrify even the most squeamish children. What got us was the illustrations.

They’ve lost some of their power over the years (meaning only that now, in my late twenties, I’m finally mature enough to look at them without shaking or throwing away the book in horror) but they’re still the stuff nightmares are made of. I chose the illustration from “The Girl Who Stood On A Grave” to be the title image for my Halloween themed posts this month, and that’s only scratching the surface of how bone-chilling some of the images are. It illustrates a fairly straightforward story, the old tale of a girl scaring herself to death by accidentally pinning her dress to a grave and imagining that a hand is holding her in place, but the image goes far beyond that simple tale. The meandering lines, the indistinct boundaries, the expression on the poor girl's face, even the hazy shapes in the background (what the hell is that, anyway, some kind of horse? I really don’t want to know) are designed with almost fiendish precision to be as frightening as possible.

They’ve lost some of their power over the years (meaning only that now, in my late twenties, I’m finally mature enough to look at them without shaking or throwing away the book in horror) but they’re still the stuff nightmares are made of. I chose the illustration from “The Girl Who Stood On A Grave” to be the title image for my Halloween themed posts this month, and that’s only scratching the surface of how bone-chilling some of the images are. It illustrates a fairly straightforward story, the old tale of a girl scaring herself to death by accidentally pinning her dress to a grave and imagining that a hand is holding her in place, but the image goes far beyond that simple tale. The meandering lines, the indistinct boundaries, the expression on the poor girl's face, even the hazy shapes in the background (what the hell is that, anyway, some kind of horse? I really don’t want to know) are designed with almost fiendish precision to be as frightening as possible. The illustrator, Stephen Gammell, has illustrated dozens of children’s books, and is as far as I can tell not a hideous creature of unspeakable evil come from beyond the stars to warp the minds of children. But he sure draws like it. This is some of the scariest stuff I’ve ever seen. It’s an often repeated trope that things unseen are scarier than things seen, but Gammell discovered a way to work this concept into his illustrations. The focus of the picture is usually frightening enough, but the way Gammell blurs the edges helps us imagine even more horrific things lurking just beyond our vision. These are not realistic people, they are twisted, misshapen, with the thick pen lines looking almost like roots tethering them to the ground. That a person can imagine such things is at once beautiful and terrifying.

The books were checked out of the elementary school library every week by some children far braver than I. I considered myself sensible for having avoided them, though morbid curiosity occasionally led to me cracking one open, spying one of the terrifying images, and slamming the book back on the shelf before retreating from the library. Imagine my surprise, then, when one Christmas I tore open a package from my grandmother I assumed was some new Nintendo game and discovered a leering skull staring back at me. That’s right, my loving grandmother had voluntarily brought the nightmares into my own house.

I couldn’t help but read and look inside—I don’t think I slept for months, but I couldn’t resist the damn things. The illustrations were so frightening that it was like looking at something from another world, something so profane and forbidden that you had to look and look again just be sure you hadn’t imagined it all. Eventually I couldn’t handle it anymore, and, plucking up my courage, for I was sure the books carried with them an evil curse, I tossed them into the trash. Not even that fully calmed my fears, and I was sure for weeks afterward that I would open my closet and find the books staring back at me, returned from their grave to haunt me for the rest of my days. So far, they haven’t come back.

It’s a decision I’ve regretted ever since. First of all, what kind of lunatic throws away a book? They’re expensive. I could have sold the thing and put the money towards a copy of Shining Force II for Sega Genesis. More importantly, as I’ve matured I’ve been able to appreciate the artistic brilliance behind the illustrations, and the insight into a child’s mind Stephen Gammell must possess to strike just the right note again and again. Adults, with their worries, so quickly forget how easy it was to be afraid of the dark as a child, but looking at these pictures captures some of that fright. Kids can imagine quite a bit, and when one wakes you up in the middle of the night, there’s a good chance what they see in their mind’s eye is at least as frightening as any of Gammell’s illustrations. This is a child’s fear of night and the dark perfectly illustrated, something almost impossible to render visually rendered to perfection. I’ve already talked about “The Girl Who Stood On a Grave” but let’s take a quick look at a few more.

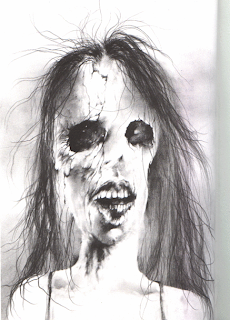

This first lovely lady was from a story called “The Haunted House” about a priest who finds a ghost. She’s become an iconic image for the series, and now graces the cover of the compilation of the three books. This is actually one of the more straightforward of Gammell’s illustrations, but note the use of the different shades of black in the eyes to hint there might be more back there, and the spindly, spider web strands of hair. It looks jagged and unpleasant to the touch, not like real hair at all. In college I stuck a picture of this beauty up beside the kitchen sink with a caption encouraging my roommates to do their dishes. I think it had the opposite effect. Great conversation starter at parties though.

This first lovely lady was from a story called “The Haunted House” about a priest who finds a ghost. She’s become an iconic image for the series, and now graces the cover of the compilation of the three books. This is actually one of the more straightforward of Gammell’s illustrations, but note the use of the different shades of black in the eyes to hint there might be more back there, and the spindly, spider web strands of hair. It looks jagged and unpleasant to the touch, not like real hair at all. In college I stuck a picture of this beauty up beside the kitchen sink with a caption encouraging my roommates to do their dishes. I think it had the opposite effect. Great conversation starter at parties though.  This one is just beautiful. I love the overgrown gravestones in the background, covered with grass that could be hair, and the gnarled, twisting roots near the woman’s hand. The story that went with this, “Rings on her Fingers” was about a girl being buried alive, but this picture is far scarier than the story. Plus it gets bonus points since we can’t tell whether the girl is walking toward us or away. I vote for away, but I’d rather not think about where she might be pointing and why.

This one is just beautiful. I love the overgrown gravestones in the background, covered with grass that could be hair, and the gnarled, twisting roots near the woman’s hand. The story that went with this, “Rings on her Fingers” was about a girl being buried alive, but this picture is far scarier than the story. Plus it gets bonus points since we can’t tell whether the girl is walking toward us or away. I vote for away, but I’d rather not think about where she might be pointing and why.  I believe this woman was supposed to be a real, living person. That’s right. In the world of Stephen Gammell, real people look like this. Good God, man. Why would you draw this? Why? This was from a story called “The Dream.” It ended with this woman coming up the stairs. That shouldn’t be terrifying in and of itself, but look at her!

I believe this woman was supposed to be a real, living person. That’s right. In the world of Stephen Gammell, real people look like this. Good God, man. Why would you draw this? Why? This was from a story called “The Dream.” It ended with this woman coming up the stairs. That shouldn’t be terrifying in and of itself, but look at her! Finally we come to “The Bride” and I’m out of things to say. This was the singular image that burned into my brain as a child and kept me afraid of the dark right through adolescence. This is just supposed to a be a picture of a human skeleton to accompany the old story where a bride locks herself in a trunk on her wedding day. But sweet Jesus! What human skeleton looks like this? Look at those teeth! She has fangs! The mature intellectual in me wants to comment on the way the spider web merges with the dress; we’re not sure where one ends and the other begins, which makes the corpse look that much more forlorn. And check out the bizarre way the feet jut out, and think about how uncomfortable such a pose would be. Then close the web browser and pray for morning, because I’ve done about as much after-dark reminiscing about these books as I care to do.

Finally we come to “The Bride” and I’m out of things to say. This was the singular image that burned into my brain as a child and kept me afraid of the dark right through adolescence. This is just supposed to a be a picture of a human skeleton to accompany the old story where a bride locks herself in a trunk on her wedding day. But sweet Jesus! What human skeleton looks like this? Look at those teeth! She has fangs! The mature intellectual in me wants to comment on the way the spider web merges with the dress; we’re not sure where one ends and the other begins, which makes the corpse look that much more forlorn. And check out the bizarre way the feet jut out, and think about how uncomfortable such a pose would be. Then close the web browser and pray for morning, because I’ve done about as much after-dark reminiscing about these books as I care to do. Many of the audio recordings of the books have found their way on to youtube, along with the accompanying images from the stories. One of my favorites, “The Window” involves vampires. As usual, the story is lackluster, but the image has so much unseen horror that it still makes me a little nervous. So if you need more Scary Stories, head on over to youtube. After spending a while writing about them, I’m ready to go to a bright room, watch some innocuous children’s programming, and forget about the spindly, root-encrusted figures that might be lurking in the darkness just outside the window.